The fourth (4th) edition of the Newport Jazz Festival took place in 1958. A sizeable bit of it was included in the film Jazz on a Summer's Day, but not all. If, for instance, we look at the At Newport albums released by Columbia from that year, it's obvious that even though the selection in the film is most welcome, it is incomplete. One of the reasons is that, due to technical issues, footage from the first day was deemed unusable (last-minute reinforcements were brought and things did work from the second day onwards). Alas, one of the bands playing on the first day, July 3, and, therefore, not in the film, was the short-lived Miles Davis sextet Cannonball Adderley, John Coltrane, Bill Evans, Paul Chambers and Jimmy Cobb: the Kind of Blue band.

Not long ago, some unused film from that festival resurfaced, but its still pending research and/or release, as far as I know. In any case, we do have the sound of Miles's sextet.

|

| Listen on Qobuz/YouTube |

It looks like Miles Davis, together with his partner at the time, Frances Taylor, spent more than one day at Newport.

|

| Gerry Mulligan, Frances Taylor, Miles Davis |

|

| Frances Taylor and Miles Davis (source) |

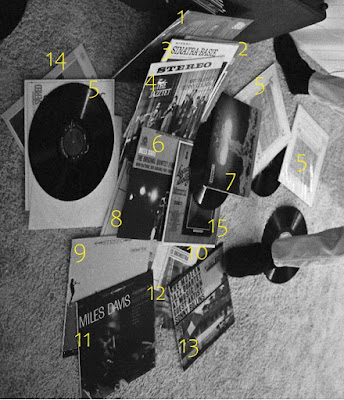

Thanks to improvements in the quality of screens and the remastering of films in HD, today it's possible to catch details that may have gone previously unnoticed (like in this photo by Herman Leonard or this footage of Monk). As it happens, on Jazz on a Summer's Day, during Thelonious Monk's performance, we can see Miles Davis, Frances Taylor, possibly Symphony Sid doing a beeline to greet Miles and, on the bottom left corner, bassist Bill Crow, who would perform as part of Gerry Mulligan's Quartet with Art Farmer (they're in the film).

|

| [1] Bill Crow [2] Miles Davis [3] Frances Taylor |

|

| [1] Bill Crow, [2] Miles Davis, [3] Frances Taylor, [4] Symphony Sid(?) |